People assume abuse and harassment will fade with the last generation of men who got away with it. They picture an old guard—men in their seventies, out of step, grandfathered into power.

That’s a comforting fantasy. But it is a fantasy. At Eastman, I saw students in their twenties reenacting this behavior. Defending it. Turning it into a bizarre performance.

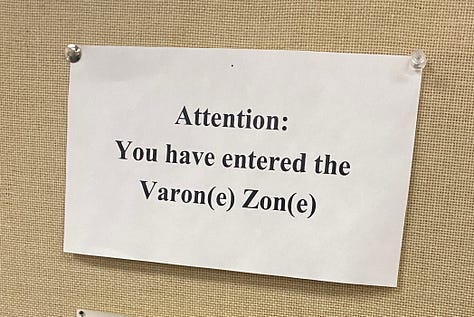

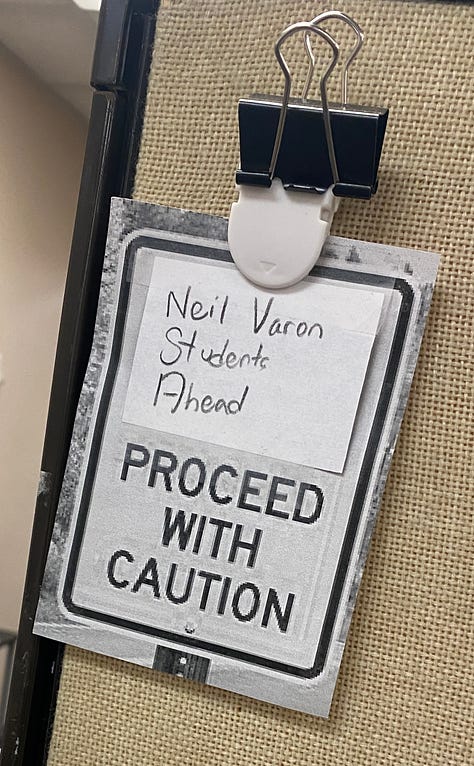

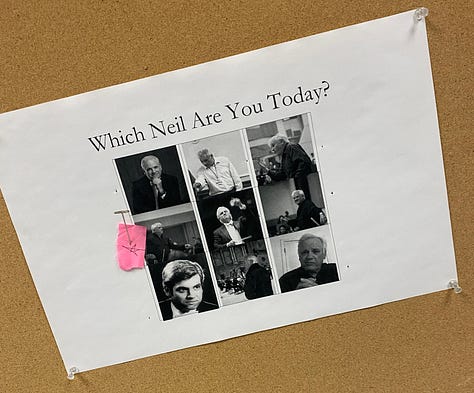

The cult of personality around Neil Varon didn’t just survive the harassment investigation—it intensified. His students displayed signs that read “The Varon Zone” and “Which Neil Are You Today?” around their cubicles, long after the university’s own investigation confirmed he’d violated policy.

One administrator worried they would become “a lynch mob.” The school took no action. The master’s student who renamed our group chat “Gibson impregnated” announced to the class—unprompted, after a confirmed harassment finding—that he had “no qualms” with Varon.

This isn’t a glitch in Eastman’s culture. It is the culture. A place where abusive behavior isn’t just tolerated—it’s cultivated.

Students learn early that loyalty to power matters more than the most basic sense of ethics or decency. They learn how to survive proximity to men like Varon: mimic their moods, laugh at their stories, avoid saying anything that might make them uncomfortable.

It was coercion—thinly veiled as tradition. Abuse of power reframed as pedagogy.

What happened in that studio wasn’t just about Neil Varon. It was about the school that protected him.

The administrators who ignored warning signs.

The eerie silence that passed under the guise of "professionalism."

The ambitious students who played the game without a moment of hesitation.

The retaliation—petty, destructive, pointless—that followed when I didn’t.

Please go to thefire.org/rochester to tell Eastman this culture needs to end. Now.

The text below is taken directly from my complaint against the Eastman School of Music, submitted to the New York State Division of Human Rights under penalty of perjury. I filed the complaint after being illegally expelled from the school with no process, warning, or prior disciplinary action.

Paragraphs are numbered as they are in the original filing. Redactions are marked in brackets. Some pronouns have been changed for anonymity.

D. Intimidation, Retaliation, Abuse of Power in Varon’s Studio

32. Varon insisted that his studio—a group of students under a private teacher—was “a family.” The result was cult-like behavior. Students deferred to Varon, protected him, and withheld even innocuous information if they thought he would disapprove. Even professional staff would not confront his behavior when it was unreasonable or unprofessional.

32.a Note: While Varon’s intimidating behavior may not have been unlawful on its own, it was part of a broader climate in which he could act with impunity. Retaliation for my later protected activity was so inevitable, multiple Eastman officials openly anticipated it but offered no intervention or protection. (See ¶61, 74, 99.a, 124–125)

33. Varon repeatedly held the orchestras past their scheduled end time. I observed an egregious incident, in which he looked at the clock, saw he was five minutes over, and said, “I know we’re over time, but I want to tell you a story”—then held them for twenty more minutes.

34. Early in my tenure, I had heard many complaints and witnessed the problem firsthand. I offered to politely speak up in rehearsals, as a teaching assistant, if Varon ran over time. [A TA] strongly advised against this, saying “He knows,” adding that he felt entitled to control the group’s schedule however he saw fit, as their director…

Varon insisted that his studio was “a family.”

The result was cult-like behavior.

34.a Note: Eastman leadership recognized this as an ongoing issue. In our first meeting, John Hain, Senior Associate Dean, said his inbox was “overflowing” with complaints from students. The school offered no meaningful action. Varon would later engage in similar tactics in retaliation for my taking accommodations after his harassment. (See ¶110–116)

35. [A staff member] once told [a TA] that students had complained… about Varon holding them late. They discussed it and agreed not to tell him, fearing immediate hostility toward themselves or the students who complained.

36. In another incident, when a faculty coach failed to show up to a rehearsal, I asked [a student] to notify Varon. They refused, responding, “he can’t handle it right now.” I had to insist that Varon was the only one who could resolve the situation before they would contact him.

Long after the formal harassment finding, his students had signs around their cubicles that said

“The Varon Zone”

“Students of Neil Varon,”

and “Which Neil Are You Today?”

37. In our earliest conversation, [a student] told me [redacted]. They begged me not to tell Varon, fearing his disapproval would affect the opportunities he offered them in the program and his willingness to recommend them. They warned me not to disclose anything he might find unacceptable, saying it could cost support and opportunities.

38. [Redacted]

39. In the strangest example of this behavior, [a student] told me that [students] had occasionally used what they referred to as “baby talk” with Varon to keep him in a good mood. I witnessed a brief exchange of this behavior between them later. I would not have fully understood the interaction without their previous explanation, but it was still unsettling.

40. Even after Varon was placed on leave—following my published account, a university investigation, and a confirmed violation of harassment policy—his students, all male by that point, displayed celebratory signs around their cubicles. They read “The Varon Zone,” “Students of Neil Varon,” and “Which Neil Are You Today?” with various photos of him.

[An administrator] worried that Varon’s students would become “a lynch mob.”

The school took no action to prevent the anticipated retaliation.

99. …I reached out to [Varon’s students], explained the situation, offered to meet to discuss it openly, and proposed logistical adjustments. I explicitly said that following the complaint, I hoped to simply get through the degree and continue to access program resources without further friction. I asked them not to share the information and to avoid prematurely raising the topic with Varon as a courtesy to him. No one responded.

99.a Note: The school made no effort to facilitate any conversations, aside from suggesting that I have a private, unstructured meeting with Varon immediately after reporting, which I declined. [An administrator] later said that intervention from the school was needed to pre-empt a retaliatory dynamic in the cohort—worrying that the other students would become “a lynch mob”—but no action was ever taken. (See ¶125)

Dvir—who had renamed the studio chat “Gibson Impregnated” the prior year—announced to the group, unprompted, that he had “no qualms” with Varon because he’d “had a great year.”

100. Shortly after that, I saw a Google Doc called “Rebecca Points” visible in [Yonatan] Dvir’s email when he had it open in the ensemble office, our shared workspace. He did not share the contents of the document, but seeing it was unsettling.

Fall Semester 2024

278. Eastman hired Jerry Hou, conductor from Rice University and Eastman graduate, as interim instructor of orchestral conducting for the 2024–2025 academic year.

279. In our first class—a small meeting of myself, Hou, and three male students—Dvir—who had renamed the studio chat “Gibson Impregnated” the prior year—announced to the group, unprompted, that he had “no qualms” with Varon because he’d “had a great year.” Hou actively facilitated the conversation and did not challenge or redirect Dvir’s remarks.

280. I gave Hou the benefit of the doubt and, in our next private meeting, I explained the harassment complaint, its mishandling, the ongoing fallout and the effect it had had on my work. He quickly changed the subject.

281. In the very next class, Hou and Dvir discussed Varon’s strengths as a teacher in front of the group. I sent Hou a follow-up email, which I later forwarded to Ardizzone, stating that while I did not expect negative remarks about Varon, the open praise normalized abuse and disregarded my experience. Neither Hou nor Ardizzone responded. I limited contact with Hou and the class going forward.

281.a N.B.: Guest conductor Tito Muñoz later said he and Hou had an extended conversation about Varon, and that Hou, as Varon’s former student, “had nothing good to say about him.” Despite his personal views, Hou apparently felt pressure to speak positively of Varon while employed by Eastman, even at the expense of my dignity and respect in his classroom.

(End of DHR excerpt)

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) is publicly advocating for Eastman to reverse my unlawful expulsion.